A country’s economy is more likely to expand when a government is about to collapse.

That is according to Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Economics who wrote a note to clients on Tuesday that demonstrates that, actually, a government with a large majority does not automatically lead to economic growth.

Prime Minister Theresa May’s slogan for the snap general election on June 8 of “strong and stable leadership” is touted as the reason why Britain’s economy will prosper under a government with a large Conservative majority. This is something that is very likely, according to the raft of polls on voting intentions for the last two weeks.

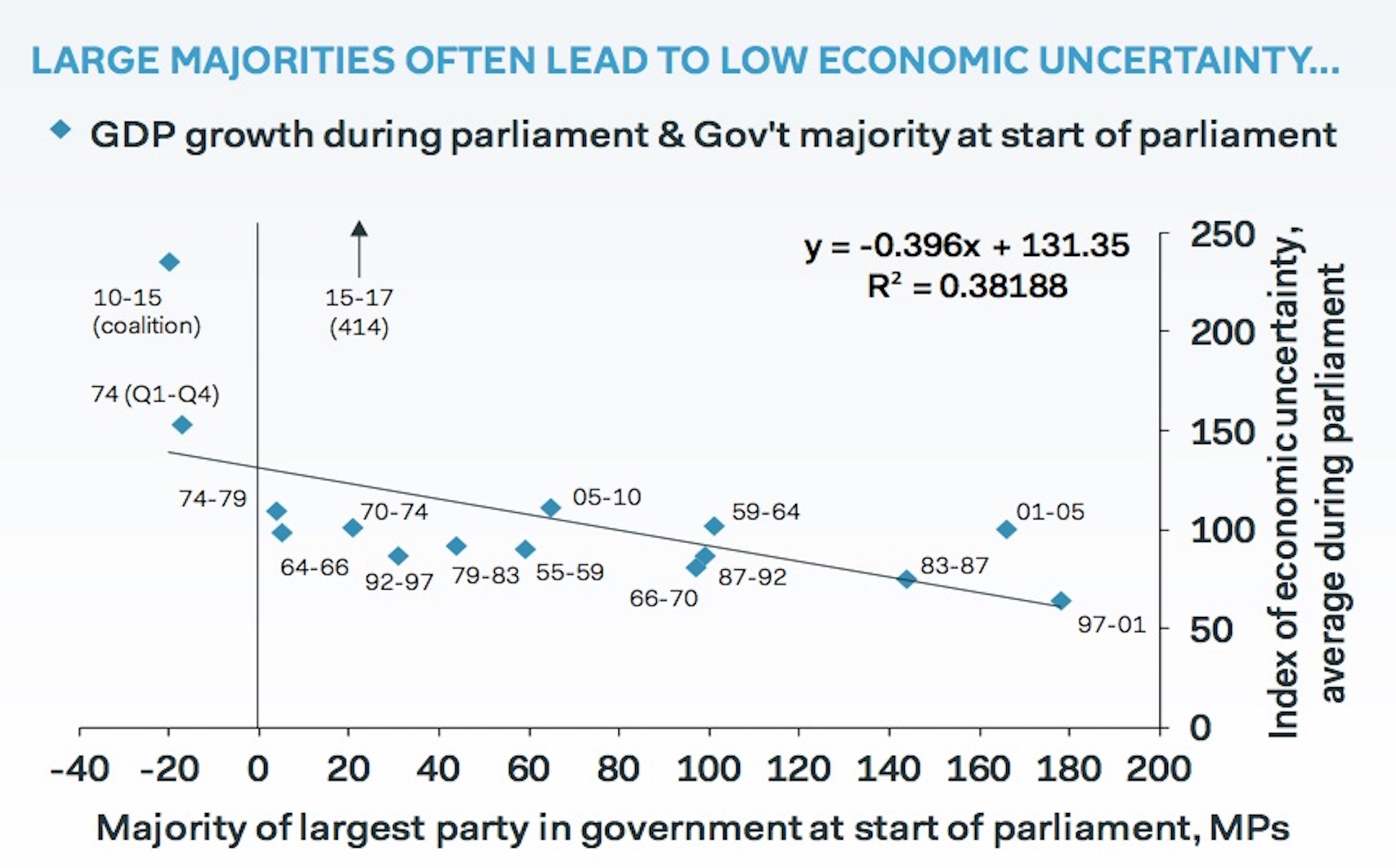

But Tombs points out that “strong economies usually lead to large majorities, not the other way round.” In the first chart he shows how UK governments with large majorities naturally lead to low economic uncertainty:

"In theory, economic uncertainty might decline when a government has a large majority because the risk of a sudden election-either being called by the Government or resulting from by-elections-declines," said Tombs.

"Firms, therefore, might be more willing to invest, safe in the knowledge that a new government with different tax and regulatory priorities will not suddenly take power. Households also might be willing to make big financial commitments, if they have greater clarity over their future finances too. In addition, governments with large majorities also might be better able to push though structural reforms which incur short-term costs but that stimulate the economy over the medium-term."

But it is not as simple to say that governments with large majorities will mean the economy expands automatically.

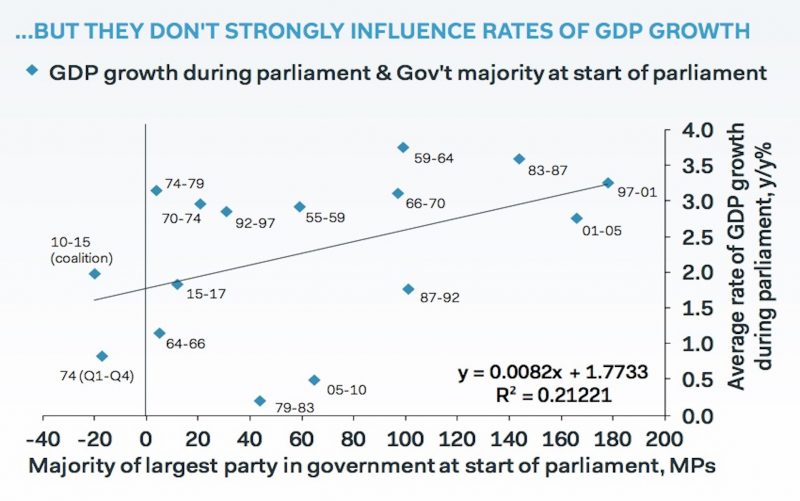

In the following chart, Tombs points out that Britain's economy has grown when even when "several governments have teetered on the brink of collapse:"

This, therefore, shows that a government with a large majority does not necessarily cause an economic expansion.

"The economy grew rapidly between 1974 and 1979, despite high policy uncertainty. In addition, year-over-year growth in GDP averaged 3% between 1992 and 1997, even though John Major's Conservative Government started with a majority of just 21 MPs and lost its majority by 1996," said Tombs.

"The loose positive relationship between majorities and GDP growth, therefore, likely arises because economic cycles usually are longer than political cycles. Strong economies usually lead to large majorities, not the other way round.

"All told, then, the economy will not show renewed vigour, just because the Government likely will increase its majority next month."